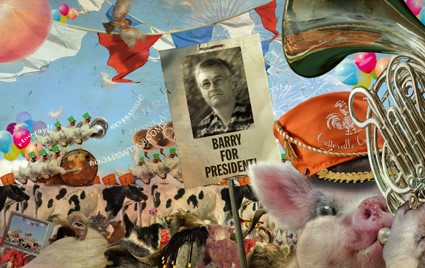

Barry Downard

Chicken Scratch Fever

Interview by Logan Kaufman

The luckiest person on the planet, he lives with his wife, two Border Collies, a Lesotho mountain dog, cats and a transient population of wild and not-so-wild animals on a small farm in the beautiful Dargle valley in the KwaZulu-Natal Midlands, South Africa. Trained as an interior designer, he designed houses, shop interiors, exhibition stands and fashion shows, and played drums and worked as an art director before drifting into fashion and advertising photography.

In 1993, he became inspired by the story-telling possibilities of digitally manipulating his photographs, and developed a style of photo-illustration. His technique consists of taking lots of photographs, throwing them into a photo-snaffling machine, stirring it up, and sticking it all together with computer glue. He combines a love of detail with a fascination for non-verbal communication. He also likes a good laugh. He is currently working with major clients, ad agencies and publishers in the UK, USA, South Africa and Australia, as well as working on illustrated children's books, creative concepts and other personal publishing projects.

His first book, an illustrated version of the "Little Red Hen" story for Simon & Schuster (New York) was launched in March 2004, with a follow-up already in the works. His own illustrated story concept, Carla's Famous Travelling Feather & Fur Show, about a ballet-dancing chicken and her entertainment roadshow, with iBooks in New York was released worldwide in March 2006. (Both books are available on online bookstores such as amazon.com, as well as major bookstores, including Adventures Underground.) His "Cow Planet" range of greeting cards, calendars and posters, is available worldwide in poster & card stores, as well as online.

Logan: Is it safe to say you have a flock of chickens acting as models somewhere?

Barry Downard: Firstly, I need to emphasise that no chickens were harmed in the making of the books, in fact they all had a real good time. Truth be told, the books were all the chickens' idea. I awoke one morning to find a delegation of disgruntled, bored chickens at the back door. As you can imagine, a disgruntled, bored chicken is not to be taken lightly, so, chicken philanthropist that I am, I set out to resolve the situation by finding some sort of stimulating pastime or endeavour for them.

We tried bungee jumping, macrame evenings, ballroom dancing, watching Larry Chicken Live, but all to no avail. Then one day whilst we were all sitting around, idly paging through Italian Vogues for inspiration, Carla (a real character of a chicken) suddenly got the inspiration... modelling!

We tried bungee jumping, macrame evenings, ballroom dancing, watching Larry Chicken Live, but all to no avail. Then one day whilst we were all sitting around, idly paging through Italian Vogues for inspiration, Carla (a real character of a chicken) suddenly got the inspiration... modelling!

She had a bit of chat with the others, and before I knew it, I had been presented with a manuscript, plus ideas on art direction and photography. How could I refuse? Plus I was faced with a whole flock of them... and did I mention they were disgruntled and bored?

Logan: Photographing disgruntled and bored animals probably wasn't too much of a stretch, since you were at one time a fashion photographer, correct?

Barry Downard: Er, fashion, yes. I enjoyed the fashion photography because there was often a fair amount of freedom/creative license, visual storytelling potential, and you got to travel a bit. (Fashion shoots in the Seychelles... I really hated my job.) But as a born-again cynic, I'm allergic to the whole concept of fashion (fashion - facile - fascism?). I won't be drawn on your implied correlation of "disgruntled and bored animals" and models! Some of my best friends are "disgruntled and bored animals".

Logan: Were you into photo manipulation when you were doing fashion photography, or was your work fairly straightforward at that time?

Barry Downard: It was mostly traditional photography, with a bit of process experimentation (cross-processing etc) as most of that period was before I became computer literate. Once I had discovered the joys of the Mac, I began to dabble a bit with manipulation, but at that stage I had lost the appetite for putting up with fashion industry bullshit, and was enjoying exploring new worlds of imagery. Disgruntled and bored animals, f'instance.

Logan: Along with your children's books, you've done a lot of freelance work. Is that where your style developed the most along the way?

Barry Downard: I suppose that it's all pretty much interlinked. My style probably derives from my interest in non-verbal communication, and the detail required to tell visual stories, or set up the starting point for a story that the viewer/reader can pick up and run with. I've always tried to work as intuitively as possible by letting feeling override the technical. A lot of digital work relies too much on overt technical wizardry.

Logan: You call your technique photo-illustration. Did you ever have much interest in traditional illustration?

Barry Downard: Growing up in a non-arty family, I was never exposed to art, and never really explored it myself. Towards the end of high school (secondary school?) I started drawing and playing with hand drawn letterforms. My mom thought I was pretty good. After school I had to do national military service, and carried on drawing to help pass the time whilst on guard duty. Dodgy stuff it was. Then, I still don't know why as I had no idea about the design/creative professions, I decided to go to a technical college to study interior design. This was before the days of the Mac, so obviously I was exposed to more drawing, and interior rendering and stuff. I enjoyed it and was OK at it, but it wasn't my strength... I could draw interiors, and natural form, but was seriously dodgy when it came to the human form. But interior rendering gave me excellent grounding in perspective, and creating the illusion of depth. I was much more interested in photography (which was a secondary subject).

Logan: Did you ever play around with doing photo collage or anything like that?

Barry Downard: (Silly version) No, I never went to photo collage, I studied interior design.

(Straight version) Not really collage... I experimented with printing multiple images onto one page, but more like sequential comic style panels than a collage collection of stuff.

Logan: Is there more-or-less a camera always around your neck, or do you go seeking images after you've got an idea?

Barry Downard: I don't normally carry a camera with me, unless I'm heading somewhere I think would have some interesting stuff to shoot. But when I do have a camera with me, I tend to shoot a lot of stuff which I think I might be able to use one day. I also seem to have quite a photographic memory, so I file away places and things so that I know where to go should I ever need to shoot. Sometimes I'll go looking specifically for something, but I often find what I need in my library of stuff I've shot over the years.

Logan: For something like a chicken, where they aren't big fans of holding still unless they are sleeping, how many pictures do you have to take before you get just the right image you're looking for?

Barry Downard: As any photographer will tell you, you need to build a relationship with your model, and I have developed a great rapport with my chickens! But with any animal (or children) photography, you start with the understanding that you will only catch what is provided, and not necessarily what you want. The final image is of necessity only an idea, which then is nudged along to work with what you get. So you watch carefully, anticipate, and get ready to grab what shot you can. In any case, you just keep shooting and then take the bits that work, and stick them together with computer glue. The rest you store away for possible later use.

Logan: Along with chickens, you've done a bit of art involving cows. Did you grow up on a farm, or were animals something you grew to appreciate?

Barry Downard: I grew up as a city boy, and only moved out to live in the countryside when I was a forty-something. I'd always enjoyed having dogs and cats around, and have always had an interest in animal welfare, and conservation issues. In fact I generally prefer animals to humankind, or as Tom Waits says, "There's one thing you can say about mankind, there's nothing kind about man". I'm now surrounded by dairy farmers, and observing cows at close range, I became surprised to notice how much personality they have (cows, not dairy farmers).

Logan: At what point did you look at these images you were making and decide to use them in a storytelling manner?

Barry Downard: The very first (what is the "very first", and why would "very first" be any different to just "first"?) image I scanned into my brand spanking new Mac was a black & white shot I'd taken of some cows. Fiddling with Photoshop for the (very) first time sent shivers up my doobrie, and a new universe of possibility presented itself to me. (Adobe aren't paying me to say this by the way.) As mentioned, I had always been drawn to exploring the storytelling potential of images (and groups of images), and I could see that I now had the tools to explore further.

Logan: Was illustrating The Little Red Hen a fairly easy decision then?

Barry Downard: My agent had presented Simon & Schuster with a rough version of a story I had written and had mocked up. They weren't sure about that story, but liked the visuals, and they suggested taking an old traditional tale and giving it my visual treatment. Little Red was their idea, and I could instantly see the potential for some quirky stuff.

Logan: What was the gist of your story that you had written?

Barry Downard: It was about Cairo Chicken, a chicken who was a born entertainer. She didn't just hatch, she "jette'd" out of her shell like a cross between a Vegas showgirl and a ballerina. She's bored to tears with traditional "roost and scratch" barnyard life. One day the ballet of "Chicken Lake" comes to the yard, and she realizes her destiny is to be an entertainer with her own roadshow. The story was eventually picked up by Milk & Cookies Press (iBooks/Byron Preiss Visual Publications), and the name was changed to "Carla". They had a problem that Cairo was too middle-eastern, and "would be difficult to pronounce". Huh? (Research note: I checked to find that there are around 5 towns in the USA named "Cairo".)

Anyway, it was published and distributed just before BPVP fell over in a cloud of Chapter 7 bankruptcy in early 2006. It's out there folks, and apparently selling, although I'm not seeing any of the moolah.

Logan: After they gave you the word go, how long did it take you to complete the full book?

Barry Downard: Simon & Schuster gave me the "go" on The Little Red Hen and that took me about 3 months.

Logan: Did you get a chance to rework the story of The Little Red Hen, or did they just want to use a previous version for the text?

Barry Downard: Because it is a traditional tale, there are several versions. The publisher found a version that they liked (and which I presume had no legal implications), and I worked with that. My next book for S&S is The Hare & the Tortoise, which I've retold.

Logan: For a story that you write and do the pictures, like Carla - do you try and develop them together at the same time?

Barry Downard: Yep, I have a constant tussle in my head between words and images. (As Elvis Costello once said, "Great to visit, but you wouldn't want to live there".) I usually have the overall idea of where it's likely to go (both words and imagery), but I find with the technique I use of comping photographic images, that letting the imagery and words bounce off each other leads to quite a fun evolutionary process. I just follow along behind and pick up the good bits.

Logan: After you've played about with the words and pictures a bit, when do you decide that you are done? Digital manipulation seems that it would have the curse/blessing of being ever open to more toying, so setting the mouse down seems like it could prove difficult.

Barry Downard: One of the critical keys to using Photoshop is "Knowing when to stop". I think that's probably critical in most media, but it certainly is in Photoshop. The determining factor for me is when I feel that the communication is right. That comes from the old "left brain, right brain thing"... it's gotta look good, and it's gotta tell the story. But you're right, there's an awful lot of awful Photoshop work out there that gives Photoshop a bad name, and me a hard time, as a lot of art directors hear the word "Photoshop" and immediately ping me with scepticism based on their previous experience.

Logan: Do a lot of your story ideas come directly from imagery? Looking at a scene or picture and imagining around that?

Barry Downard: Ideas often come from an instant where something happens, or something is said/seen and some sort of juxtaposition occurs, it all gets swirled up and out of context, to spark something all of its own. The best ones usually creep up unannounced, and unsought. My Carla's Famous Traveling Feather & Fur Show story started as a thought around a series of "Dances with Chickens". That led to a mock poster for the ballet "Chicken Lake" (with Margot Fonthen and Rooster Nureyev)... and an AD at Penguin (NY) saw that and said that there was a story waiting to happen.

Logan: Are you in a position then where story possibilities are quite plentiful, or do you weed them down and try to find ideas that work best as a full story?

Barry Downard: I think story possibilities are all around, if you're open to the available stimuli. I've got all the words... I've just got to get them in the right order! There's a constant process of stirring around, and figuring out if the idea is strong enough, and substantial enough.

Logan: Overall, what is the appeal for you to get these story ideas out to kids? Were you around kids who enjoyed stories, or were you remembering your own enjoyment of them?

Barry Downard: I have a great interest in animal welfare, and biodiversity conservation issues, and I've got some sort of idea of hopefully getting kids to look at animals as equals. My dedication in The Little Red Hen is about loving, caring for, and respecting animals, "... after all, animals are people too." My Carla Chicken book's dedication is to "... animal-friends everywhere". Apart from that, Tom Waits puts it well with the line, "innocent when you dream". I've had some great emails from schoolkids who have found something special for themselves in the books, and that is worth more than money to me. I actually grew up without many storybooks around, and I was always playing soccer. I'm finally catching up, as I have acquired a tasty selection of kids' books, which I enjoy from the illustration and story point of view.

Logan: Do kids pick up on that at all? What do they usually react to?

Barry Downard: I think so, although I admit that it may well be more of a subliminal thing. I think that one of the biggest problems for animal welfare is that humans are largely brought up to regard animals as "things", rather than "differently-abled fellow inhabitants". I'd like to find a way to portray a link to animals that would encourage more empathy, and that goes beyond the typical Disneyfication of anthropomorphism. I don't know if I'm getting it right, but it's a work in progress. I find a lot of reaction to the detail that is there for those that want to look.

Logan: Have you had an opportunity to do readings of your books at libraries or anything like that?

Barry Downard: Nope. But living in South Africa probably accounts for that. The market here is so small, that the distributors find it barely worth their while to engage with it. The responses I've had in personal letters from schools in the US would certainly encourage me to make the effort to visit schools and libraries, if I lived there.

Logan: For the Hare and Tortoise tale, what are you doing with the story to change it around?

Barry Downard: Unlike Lane Smith's brilliant Stinky Cheese Man and Other Fairly Stupid Tales, the motto is still the same. I've just set it in a more contemporary paradigm (now there's a word!) by surrounding the race with all sorts of media and marketing hype. The race gets TV coverage on "Don Key's Wide World of Sport", and there's a "Carrots-R-Us" billboard in there somewhere. Flash Harry Hare is also the modern branded sports personality, complete with designed logo brandname, and printed up PR "hero sheets" for the fans, and a "Bunnies dig me" high tech running vest.

Logan: Did you have to go out and find a rabbit and tortoise, or can they already be found on your farm?

Barry Downard: Ah, the models. The tortoise is actually a combination of a very detailed resin model, and some elements of a real live tortoise (with some human elements thrown in for effect). I've only ever seen one tortoise on my property, one time a couple of years back. He has since vanished. Blink and you miss! As for the hare...you'll have to wait and see...

You can learn more about Barry Downard at barrydownard.com

Interview conducted by email, December of 2006

Copyright © 2006 Adventures Underground

More Interviews