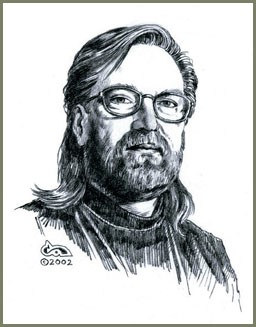

Clyde Caldwell

Education of an Illustrator

Interview by Logan Kaufman

As a boy growing up in a small town in North Carolina, Clyde Caldwell roamed the red sands of Mars and explored the world at the Earth's core with Edgar Rice Burroughs, and was whisked away to other worlds, alternate dimensions and adventures in the future by Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein and Arthur C. Clarke.

After several years of working as a commercial illustrator for ad agencies and doing fanzine work in his spare time, he began to get cover assignments from professional fantasy & science fiction publishers.

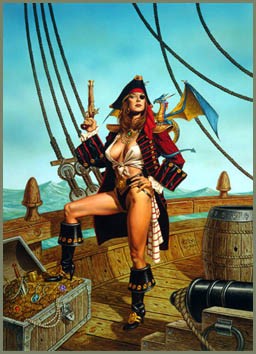

Over the past 25 years, Clyde has produced hundreds of cover paintings for his chosen field, and is best known for his portrayal of strong, sexy female characters. His work has appeared as book covers for such publishers as Ace, Avon, Popular Library, Warner books, Zebra, Houghton-Mifflin, and Doubleday.

Logan Kaufman: How did you first get into professional illustration?

Clyde Caldwell: Although I majored in Fine Arts in college, I always had been a big fan of science fiction / fantasy literature and comics. When in graduate school working on my MFA degree, I decided I wanted to go into illustration upon graduation, which didn't make me too popular with my stuffy, fine arts professors.

While still in graduate school, I started working for various fanzines. After graduation, I continued doing the fanzine work, while getting my first job as an illustrator in the advertising department of the Charlotte Observer/News newspaper. I moved on to a job in an ad agency, all the while looking to break into the science fiction / fantasy market on a professional level.

I finally got my break by doing some covers and interior illustrations for a small SF anthology magazine published in Boston called Unearth. It only lasted eight issues, but I consider that my foot in the door to the professional Science fiction / fantasy illustration market.

Logan: What had made you think that genre illustration was something you could really make a living at?

Clyde Caldwell: I never really gave it too much thought. I knew local freelance illustrators who were able to make a living, so I figured if I were doing work on a national level, I'd be able to make a living at it. I assumed the people I saw doing science fiction / fantasy cover work on a regular basis were able to do it for a living.

I've got a funny story along those lines, though. I'd been working in the field for a year or so and a fellow from the local library (in Gastonia, NC...my home town) called and asked if I'd put on an exhibit of my work at the library. He was a big Edgar Rice Burroughs fan and was familiar with my fanzine work, as well as my professional work.

I said okay and put up the exhibit. During the reception the fellow asked me, "What do you do for a living?". I was a little puzzled, so asked what he meant. He couldn't quite wrap his mind around the fact that I did illustration for a living. To him, I guess artwork was something one did as a hobby, and you needed a "real job" in order to make a living.

Logan: Did the job at Unearth open any immediate doors, or did you just hit the pavement looking for new jobs after they went under?

Clyde Caldwell: I did quite a bit of work for Unearth...at least three covers and some black & white interiors. There was one issue for which I did the cover and illustrated all the stories. For each story, I tried to use a slightly different illustration technique. It was a good showcase for me. A New York agent saw my work and contacted me wanting to represent me. He started getting me paperback cover work and work for Heavy Metal magazine.

Logan: Had your degree in art really prepared you for book illustration and doing work at Heavy Metal? Or do you consider yourself more self-taught in that regard?

Clyde Caldwell: If I had it to do all over again, I would go to a two-year technical school that offered a good course in illustration. I think that would have been enough to provide the tools I would need to enter the field.

It would be hard to say that I'm "self-taught", because I learned a lot about abstraction and design in fine art, but not so much about painting and drawing realistically (since all the emphasis was on abstract and non-objective art when I was in school)...and everything I know about color has been learned by trial and error. I do have to say that the time spent in art school allowed me to develop my talent a bit before I had to go out into the real world...and allowed me to mature a bit. In an odd way, because I really didn't feel that fine art was for me, it pointed me down the road to a career as a fantasy illustrator. It just took me a while to figure out what I really wanted to do.

Logan: Had you originally gone in with the notion of a career in fine art, or did that just seem like the place to go if you wanted to become any sort of artist?

Clyde Caldwell: When I graduated from high school, I was playing guitar, singing and writing songs in a rock band. I was more interested in becoming a rock star than an artist! However, that was in the Vietnam era, and if you weren't in college, you were bound to be drafted. I wasn't really an anti-war type, I was pretty politically apathetic in those days...but didn't have a huge desire to go to war if I didn't have to.

I really would have liked to have gone to the Ringling School of Art in Sarasota to become a commercial artist, but didn't have the money. I spent my first two years of college at Gaston Community College, which was just down the road from where I lived, and was all I could afford. I then transferred to UNC-Charlotte, where I got a BA with a major in Fine Arts.

I intended on trying to get a job in commercial art after graduation, but one of my professors talked me into going to grad school. While in grad school, the lottery system was initiated. I had a high lottery number, so wasn't drafted.

Logan: You mentioned learning about color by trial and error: was there a big learning curve for you overall in regards to professional illustration?

Logan: You mentioned learning about color by trial and error: was there a big learning curve for you overall in regards to professional illustration?

Clyde Caldwell: My dad was a printer, and he used to work with a fellow named Sam Grainger who did inking for Marvel Comics. When I was a kid, I used to send Sam drawings of superheroes to critique. I sort of grew up with a passing familiarity with commercial art, but it was mostly nuts & bolts stuff.

I had a summer job at a photolith shop and learned all about color separation, back before it all went digital. We shot the artwork on a big flatbed camera, developed the huge negatives by hand, etc. It was a great learning experience. When I actually got my first job in the advertising department at the newspaper, I knew more about doing hand color separations (with hand cut rubylith masks) than the people who had been working there for years. Plus, I always said I learned more in the first six months working at the newspaper than I had in my six years in college! There's nothing like on-the-job experience.

I think the fanzine work helped me a lot in developing to the point that I could do professional science fiction / fantasy illustration. But paying my dues in the advertising field helped me when I broke into the science fiction / fantasy market as well. I was used to working with deadlines, picky art directors, etc...though I never was a fast artist.

I had somewhat of a natural sense of composition and design. That came fairly easy for me. Early on, I did a lot of black & white work, which also came pretty naturally. However, I don't feel like I have a natural sense of color like some of the artists I've worked with in the past (Keith Parkinson and Brom come to mind). I had to work at developing the color sense...and I'm still working at it!

Logan: How did you come to work for TSR?

Clyde Caldwell: I was freelancing in North Carolina and a friend of mine, a fellow artist, showed me a copy of Dragon Magazine. I had heard of Dungeons & Dragons, but knew very little about it. My friend decided that he was going to submit some samples to Dragon, in hopes of getting a cover. I had been working professionally in the field for several years and was looking for outlets for my work...so I sent some samples as well.

Kim Mohan at Dragon bought the rights to a painting called Dragon Spell (my first Dragon cover), which had actually been done for another project that fell through. He also gave me an assignment for the TSR calendar for that year, and I started doing fairly steady cover work for the magazine.

I think I did around nine Dragon covers over a three-year period. During those 3 years, TSR contacted me several times to see if I would like a full-time job as a staff artist. I was pretty happy freelancing in North Carolina, so the first couple of times they offered, I turned them down.

I guess third time's the charm. They offered to fly me up to Wisconsin for a job interview. I had no intention of taking the job, but flew up to meet Kim Mohan and some of the other people I'd been working with at Dragon. But when I met the other artists working at TSR, I thought, "This is for me!" So I took the full-time staff position and moved to Wisconsin.

At the time, I was still doing some advertising work in addition to my science fiction / fantasy work. Taking the staff position at TSR was an opportunity to do fantasy art full time, which was my goal.

Oh...and that guy who showed me the Dragon Magazine didn't get any cover work from them! Go figger...

Logan: Your biography says you left TSR in 1992 to pursue a freelance career. Were you an actual 9-to-5 employee, or did they have exclusive rights to your artwork? How did that work?

Clyde Caldwell: Yes, I worked at TSR in-house for almost ten years. The difference between being a staff artist and freelancing is that as a staff artist you get paid a steady salary and you get benefits, like health insurance. As a freelancer, you just get paid for the individual jobs you do and you're responsible for your own health insurance, retirement, etc. Though I sometimes miss the security of a steady paycheck, I prefer the freedom of freelancing.

The TSR artists all worked in a studio together. That's one reason I took the job. I'd been fairly isolated in North Carolina in terms of my interest in fantasy art and it was great working with other artists who had the same interests. We all got along very well. It was a great experience...and though I prefer the life of a freelancer, I still miss the camaraderie we had in those days...and I learned a lot from the other guys.

During the period I worked in-house for TSR, they did retain most of the rights to the artwork (with the exception of the Dragon Magazine covers). We (the TSR staff artists) were allowed to retain the rights to make limited edition prints of the art we produced, and the rights to include the pieces in art books.

In freelancing, I try to hold onto as many reprint rights as possible. Most of the time I'm able to do that, but, depending on the client, I sometimes have to give up all future rights.

Logan: What was your work day like when you were working for a company like TSR?

Clyde Caldwell: I would usually get in to work around 9:00 AM and work until 5:30 or 6:00 PM. Since I wasn't a terribly fast artist, I would usually take work home with me and draw or paint after dinner, sometimes into the wee hours of the morning. I normally painted on the weekends as well.

Sometimes I would have one painting going at work and one going at home, so that made for some long work days. Since we were salaried employees, unfortunately we weren't getting paid by the hour.

Needless to say, there were always a lot of distractions at TSR. While it was fun working with a crew of like-minded artists, it made it harder to focus and concentrate on the artwork. We also worked around a lot of game designers, editors and authors...and then there were way too many meetings!

Logan: How do you manage your day differently when you are working on your own?

Clyde Caldwell: I really got burned out with the grind at TSR. I'm not as young as I used to be, so don't do too many late nights or all-nighters like I used to. I don't rebound as fast as I once did! I find that if I get a good night's sleep, I feel a little more enthusiastic about painting the next day...and actually seem to be somewhat more focused and productive. I try to live a more balanced life nowadays.

In the evenings I put together orders from my website...and since painting isn't the most physically active career, I try to set aside an hour most days to exercise.

Logan: Now that you are working freelance, what steps are involved in getting work? I assume with your reputation, you don't need to actively pursue jobs...

Clyde Caldwell: I probably should actively pursue jobs, but I'm pretty slack in that area. Since I started freelancing in '92, there have only been a couple of times that I've been without work to do. I just do whatever comes along.

More often than not, I'll have to turn down work because I can't fit it into my schedule. Every once in a while, I'll be down to my last job and I'll think to myself, "If another job doesn't surface soon, when I'm done with this one, I'll have to go out and beat the bushes." But usually something else comes in before that happens.

Logan: Once you've agreed to tackle a painting, where do you get started?

Clyde Caldwell: It depends on the job. If I'm doing a book cover, I start by reading the manuscript and taking notes. I usually submit a couple of pencil sketches of cover ideas to the publisher. I like to start that process by doing thumbnails and roughly developing some ideas, and then bringing in a model or models for a photo shoot. After the photo shoot, I work up fairly nice sketches to submit to the publisher. They usually choose one, hopefully without any changes, and then I do the painting.

I used to have to submit a couple of color roughs, which I hated to do because they took too much time. Now I get away with just the pencil sketches.

If I have time, I try to do fairly nice production drawings, since I'm able to sell those.

Logan: What kind of changes or suggestions would a publisher typically have when reviewing a finished sketch?

Clyde Caldwell: Truth to tell, most of the time they don't make any changes. They just approve a sketch and I do the painting. However, every now and again they'll make minor changes to a sketch...and then every once in a while they'll want major changes. That's pretty rare though.

For the painting, There Will Be Dragons, I did a couple of sketches and submitted them. Jim Baen wrote back and accepted a sketch, but he said the distributor wanted a science fiction element on the cover (which was basically a fantasy painting)...and would I add a tiny spaceship in the background? I reluctantly added the spaceship, though there were no spaceships in the book!

Logan: Do you ever try and get direct author input on a piece? Is the author's vision something you take into account at all when you're working on a painting?

Clyde Caldwell: I certainly try to keep the author's vision in mind when I'm coming up with ideas. I like to try to find things in the manuscript that I'd like to paint and then bring them to life. And I always like to read the full manuscript, if available, to get a feel for the book.

In the past I've noticed that publishers usually don't like for authors and artists to get together and exchange ideas. I think the concept is that authors are too close to the material and aren't necessarily terribly visual and might not make the best choice for a cover. I do talk to authors at times though...especially when I don't have enough information to come up with good cover ideas. Most of the time they're very easy to work with and helpful.

I'm working on a cover for a book by Wm. Mark Simmons right now. I only had a partial manuscript to work from, so contacted Mark with some questions. He's been very helpful in providing information and throwing out ideas for discussion.

Every now and then a big author might make suggestions (or demands) as to what he or she wants on the cover of their book. Sometimes they're good ideas...sometimes not. In those cases I just do the best I can with the ideas I have to work with.

An author just came up to me at DragonCon and introduced herself by saying, "I want to thank you. You made me a lot of money." She thought that my cover had sold the book, and the book sold very well. Illustrators love to hear that!

You can learn more about Clyde Caldwell at clydecaldwell.com

Interview conducted by email, September of 2006

Copyright © 2006 Adventures Underground

More Interviews