Richard Sala: The Art of Mystery and Horror

Interview by Logan Kaufman, Adventures Underground

Richard Sala was born in Oakland, California and grew up in the Chicago area where his father was an antiques dealer. As a youngster, Sala spent many hours in Chicago museums, staring at the mummies, stuffed animals and caveman dioramas. He then lived in Arizona for a number of years before returning to the Bay Area, where his life-long compulsion to draw had led him to graduate with an MFA in Painting from Mills College.

Sala's paintings and prints have been exhibited internationally. His illustrations and comics have been widely published in many newspapers, books, and magazines such as Esquire, Playboy, and RAW. His animated serial, Invisible Hands, appeared on MTV's Liquid Television, and his work can also be found on the Residents' CD-ROMs Freak Show and Bad Day at the Midway. Two collections of his comics, now long out of print, were published by Kitchen Sink Press: Hypnotic Tales (1992) and Black Cat Crossing (1993). Sala produced a comic book called Thirteen O'Clock for the publisher Dark Horse in 1992, and he wrote and drew a number of full-color comic strips for Nickelodeon Magazine from 1993 to 1995. A small book of black-humored verse and drawings called The Ghastly Ones was released in 1995.

From 1995-1997, Sala created the horror-thriller graphic novel The Chuckling Whatsit. The Chuckling Whatsit originally serialized in the pages of the anthology Zero Zero; it was later collected into a single 200-page volume by Fantagraphics.

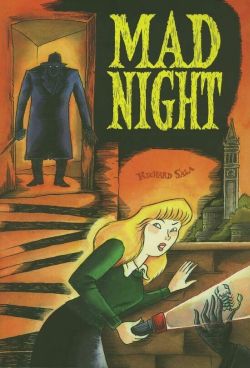

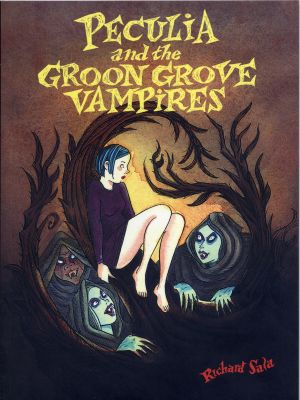

Sala completed twelve issues of the comic book Evil Eye and in July 2002, Fantagraphics released Peculia, a collection of fairy-tale like horror strips collected from the comic. Fantagraphics also published a collection of long out-of-print short stories by Sala in early 2004, titled Maniac Killer Strikes Again! In 2005, a follow-up to Peculia was released, entitled Peculia and the Groon Grove Vampires. That same year saw the publication of Sala's second epic horror-thriller, the 200-page Mad Night. Also released that year were Dracula, with Steve Niles, and a new edition of The Chuckling Whatsit.

Other projects have included a collaboration with author Lemony Snicket for the children's anthology Little Lit, and 70 illustrations for a screenplay by Jack Kerouac, titled Dr. Sax and the Great World Snake. He is working on several new releases for 2006 - 2007, including Delphine, a five-issue series co-published by Fantagraphics and Coconino Press, and The Grave Robber's Daughter, a new graphic novel from Fantagraphics. Richard Sala lives in Berkeley, California. Visit his website at: www.richardsala.com.

Logan Kaufman: For someone with a rather healthy body of work and following, there really aren't tons of things written about you, in regards to interviews and such. At the same time, you're on MySpace and run your own website. Are you a recluse in denial, or a social butterfly who everyone keeps forgetting to ask for interviews?

Richard Sala: I'm schizo, I guess. Or maybe it's my Gemini nature. I've always had just a few really good friends, but I'm kind of uncomfortable with social interaction in general. I love hanging out with friends and making them laugh and having conversations -- but if I'm put in front of a large group of people I'm a mess. During my young adulthood, of course, I did things like teach (while I was a graduate student) and I had a job that required lots of social interaction where I was very responsible and well-liked (I think). But I was a shy kid, and after becoming a full-time freelancer, working out of my home, I think I somehow began to "unlearn" a lot of my social skills. Being a cartoonist requires spending a lot of time alone in your head. I've always been extremely neurotic and after my divorce (we were together for twenty years and are still good friends) I just sort of lost interest in trying to be more social. I love my work -- and that's where I generally find my pleasure and satisfaction. At one point I began losing my voice and had to see a doctor whose diagnosis was that I had forgotten how to speak! It was some bizarre psychosomatic stress-related shit...

However, I have found the internet to be a wonderful antidote to my messed-up social skills (like a lot of fellow shut-ins, I dare say). The MySpace thing is fairly new and so far I'm enjoying it -- I don't take it too seriously -- it's mainly silly fun. But I've met some cool new people, reunited with old friends and even sold work and so on, because of it. As far as my richardsala.com website -- a friend of mine, the genius John Kuramoto, built that for me. It doesn't require much "hands-on" activity from me. It actually badly needs updating right now.

So -- in answer to your question. I AM somewhat of a recluse, but I'm not in denial about it. And nobody would ever mistake me for a social butterfly, I'm sorry to say.

Logan: What information is out there states you grew up in an abusive household...

Richard Sala: Wow -- you're the second person to ask me that in the last month -- that is, about my "abusive" household. This must be an internet thing -- maybe? Anyway, as I recall, the only place I discussed my childhood was in an interview I did with The Comics Journal years ago and maybe that is where this comes from. I don't think I did (or would) use the word "abusive" pertaining to MYSELF (although my sister and mother might). I mean, I wouldn't want to trivialize the meaning of the word. But my father was not a happy man. He was angry and irrational and would often terrorize me and my brother and sister with violence or threats of violence. This was the mid-sixties, and he was an "old school" first generation Sicilian with what they used to call "a temper", so disciplining kids by hitting them was not as foreign a concept as it is now, perhaps. I got hit with all kinds of things -- belts, hairbrushes, pieces of wood, books...but even in my high school a few years later kids would get spanked with a paddle in front of the class if they offended the teacher in some way....It was a different era.

Anyway, I guess you CAN say that my relationship with my father did mess me up a bit, because, although there was cruelty and irrational behavior, nevertheless, my father is where I get almost all of my creative side from. He knew how to draw, which always amazed me as a kid, and he had a love and knowledge of old movies and monsters and weird popular culture stuff that has come to define who I am, too. It's very complicated -- or rather it's one for the shrinks, I guess.

Logan: Was your father in an artistic field, or was drawing a hobby for him?

Richard Sala: It was a hobby, but when you're a kid even average drawing can seem like magic. I remember watching cartoons with him and he was able to draw the characters that were on TV as they appeared on the screen. That impressed me, I remember. I also remember my cousins watching in awe as he drew pictures of pirates or cowboys during one summer vacation. I think maybe that's when I realized that it was considered "cool". But he wasn't schooled in art, unless it was maybe some classes due to the GI Bill after WWII. He only had an 8th grade education and had done all this macho stuff like being in a post-war motorcycle gang, ala The Wild One, and being a lumberjack in the Pacific Northwest. I saw photos of all these adventures or I may not have believed them myself!

His drawing must have inspired me to do it myself, but I honestly don't remember a single word of encouragement or advice from him regarding art. Instead, my first real memory of being an artist was when my kindergarten teacher raved about a drawing I had done and showed it to another teacher in front of me and they both cooed over it. I think I have that moment to blame on becoming an artist!

Logan: When did you get into the horror and pop culture yourself? Was that an experience you shared with your dad, or just because your were around it, something you explored on your own?

Richard Sala: I have no idea why I responded to monsters and scary stuff, rather than, say, cowboys or baseball cards, enough to make it a life-long interest. I have my pet pop-psych theories (e.g. exposing myself to scary stuff helped me conquer my fears of real life, etc...) but I honestly don't know for sure. My brother and I started buying monster magazines when we were little, but he didn't become hooked like I did. My father would mention that he had seen King Kong and the original Phantom of the Opera with Lon Chaney when he was a kid, and I remember he liked them, but he liked old movies in general. It all seemed to be something specific to me. For example, I must have read lots of comics as a little kid -- funny animals or whatever -- but the first comic that made an impression on me -- that made me sit up and take notice -- was a Jack Kirby, pre-hero, Tales of Suspense comic. My brother and I bought all those pre-hero Marvel/Atlas monster comics and so we were there for the debut of The Fantastic Four and Spiderman and The Hulk. I bought those, too, because I loved Kirby (though I wasn't really aware who he was -- I just recognized the style), but I always missed those Atlas monster comics.

Similarly, I started clipping out Dick Tracy comics and putting them in a scrapbook when I was in the fifth grade. Again, I'm sure I was responding to the grotesque characters, the wild violence, and the borderline horror element that was in those strips.

As I grew older, I certainly tried more than once to "outgrow" monsters and comics and pop culture. I got an education. I spent more time concerned with music and girls, etc. I had a career as an illustrator. But I was continually discovering smart, "adult" ways of looking at the stuff (reading scholarly articles that took comics and horror seriously, for example, or seeing poetic, adult horror movies like Eyes Without a Face, etc, etc.) and I'd realize that maybe these weren't simply childish thrills I needed to outgrow. I became fascinated with meaning and subtext. But I also couldn't deny the visceral thrills either. I guess I finally reached a point where I felt such a deep kinship with the creators of the stuff I loved that I knew I had to join them.

Logan: I've always thought of horror and fantasy as a safe outlet for a certain amount of bloodlust. Watching a war movie makes me sick to my stomach, but I could watch zombies all day. It's safe. It's never going to happen to me.

Richard Sala: Certainly from a very young age I was able to grasp that movies weren't real. From the very beginning, I understood that movies were entertainment -- that they were created by writers and cinematographers and make-up artists and actors and so on. I assume I'm not the only one! And as I got a little older I could see that, in addition to entertainment, horror movies could serve as an outlet for our real life fears. It's such a cliche -- but it's like riding a rollercoaster -- when the ride is over, you feel braver and more alive for having "survived". Then -- beyond even that -- one can look at horror movies as modern-day folk tales, in that they are rich in the potential for analysis, as "dreams" almost, which can be interpreted and scrutinized as not only showing us our individual fears, but whatever our cultural or societal fears may be at that time.

I understand what you mean about war movies, but I've never had a problem with any fictional genre. I feel that (for me) violent movies of any kind can offer a genuine catharsis. That's why the trend of PG-13-rated horror movies is so frustrating for audiences. On the other hand, the new trend of "torture" movies (SAW, Hostel, etc), although capturing a specific mood of our time, I suppose, aren't satisfying to me in particular. I think the reason is that I can sense they were made to be over-the-top, but it doesn't feel that the filmakers have a real, obsessive need to explore this stuff (most great horror directors find something inside themselves to use). Instead it just feels like it's being done to make money and exploit horror fans. I may be wrong, but that's how it's looking to me now.

I'm also not a big fan of the "true crime" segment of horror. It's become more and more common for people who are horror fans to also be "fans" of real-life killers like Manson, etc. I have no problem with fictionalized versions of real life crimes, but my feeling that, for the most part, is, if you are into that sort of thing, your interest is in "true crime", not the "horror" genre. I could never confuse Charles Manson or Ted Bundy with Frankenstein and Freddy Krueger, but it seems like that line has blurred for some people. Naturally I find true-crime fascinating, but I couldn't ever really call it entertainment or even a safe outlet for anyone's fears. It's usually the opposite, for me anyway!

Logan: When you started to draw, were they immediately based on these fantastical type images?

Richard Sala: I drew all kinds of things as a kid, but, yes I probably leaned toward the more fantastical. I drew comics and pictures of monsters and so on. Then I got older and took art classes and that certainly broadened my perspective. The funny thing is I spent years unlearning all the cartoony elements in my work that had formed when I was a kid. And that was fine for awhile. I decided I wanted to be a great classical illustrator like N.C. Wyeth (even though I was in the Fine Arts program, not Illustration or Design). I struggled with that for a year or so -- it just didn't come naturally to me, I can see that now -- it wasn't in my nature, it didn't suit my temperment or personality. The great thing about art school is it helps you work through those things. Finally I had classes with two teachers who encouraged us to find who we were -- just by drawing and drawing constantly to see what would come up. I found myself drawing all these Expressionistic, Caligari-esque corridors and doorways, bizarre scenarios featuring operating rooms and hunched shadowy figures. Now that DID come easily to me. That was my true nature -- all that stuff I'd absorbed so hungrily as a kid. It started all coming back and I guess it never completely went away again.

Logan: How long did it take you to nail down your personal style in school? You actually have a master's degree in art -- it seems somewhat uncommon for a comic book artist to have received that much formal training.

Richard Sala: Whatever my style is, it began to be apparent in those classes I mentioned above, where students were encouraged to draw whatever came to their minds at the moment, sort of like automatic writing. It's kind of a surrealist approach for unlocking the unconscious, I guess. I show the work I did then, back in the late seventies, to people now and they say they can tell it's me, although I've certainly changed since then. It was the punk era and my friends and I hated above all things artists who could draw in lots of different styles. I hated that facility, because it's just empty craft. I felt that a "style" was simply who you were -- you shouldn't be able to (or want to) completely change your "style". It's not honest. You should be able to look at an artist's work and immediately know who it is -- it should be unique, like a fingerprint. We had a campus design group -- me and two other artists -- and our motto was "We can't help it, we HAVE to draw this way." And that sort of summed up my attitude then.

One change occured for me during my second RAW story, the one that was written by Tom DeHaven called "Proxy". I think Art Spiegelman helped guide me away from my freewheeling expressionism by pointing out that the formal aspects of comics exist for a reason -- to better communicate with the audience, to get your ideas across in a clearer manner. I think I came in with my master's degree feeling somewhat superior to comics (after all, that had been hammered in my head for six years) and feeling like I could push the boundries and do whatever I wanted. But this story was by another author and I wanted to honor that as best I could. When I look at that story now, I can see myself struggling with the formal aspects of comics. Mainly my attempt to do more-or-less straight lettering -- that looks terrible. Over the years, I've tried to keep the parts of me that are unique, but still follow the "rules" enough so that I can make good comics. I've let my style grow naturally to better suit the medium of comics. One thing I learned is that I relate much more to the story-telling in old comic strips rather than comic books. I really feel at home with that brand of straight-forward storytelling. I could never relate to those flashy mainstream comics pages that came out of the seventies from people like Neal Adams with the jagged "broken glass" layouts and heroes with clenched teeth and pained expressions bursting out of the borders. Give me a simple honest Dick Tracy-style grid of square panels anyday!

Logan: There is a photo of a you on your MySpace page with some large paintings hanging behind you. Was that more typical of what you were doing in college, or did you also do a lot of work in pen and ink at the time?

Richard Sala: That photo of me was taken in a corner of my big beautiful studio at Mills College. Yes, those painting were typical of the kind of work I was doing my first year there in 1980. The work I showed that got me accepted was all on paper -- watercolor, pen & ink drawings, etchings -- nothing bigger than 22"x30". But I was a painting major and was strongly encouraged to work in oils and work big, so I did. My painting eventually got better than the ones you see in that photo! Those are just canvas stapled to the studio wall. I'd always work on three or more paintings at once since oil takes so long to dry.

What's interesting is that those paintings look like enlarged comic book panels - so I was still thinking in "small" terms, even if I was working larger. And in fact some of those compositions eventually showed up in my first self-published book -- so they came full-circle! The other indication that I couldn't entirely abandon my love of pop culture was when the Art Department secretary, Marilyn -- a nice older lady who didn't really know anything about art, but was a sweet mother-figure for all the artists and teachers -- she came to one of the graduate shows and looked at my paintings and said, "Oh - I get it - Dick Tracy." I was surprised at that time that my influences were so obvious!

The downside of that was when I had a critique with the Photography professor who told me my work looked too much like "underground comix", which at that time was painfully over, I mean OVER -- especially in the Bay Area where it had been such a big thing for so long. Underground comix at that point reminded people of hippies and NOBODY wanted to be reminded of hippies in 1980! This professor said to me -- which I actually consider very good advice -- "Live in your own time", meaning, basically, don't do work that strives to be of part of an era you are not living in. Be aware of where the culture is now.

Logan: I know you enjoyed comics as a kid, but what actually got you into doing themself yourself after college? Like you said, there isn't a lot of love for the medium in most art schools.

Richard Sala: I was fortunate that there were some really good comic book stores in the Bay Area. Actually, a person who used to work at one of them was Rory Root who later went on to establish one of the greatest comic book stores ever, Comic Relief. Anyway, back then I would take the bus down to Telegraph Avenue by UC Berkeley to check out the book stores and the record stores, and there were two (!) good comic book stores there within walking distance of each other. I'd stop in to look for old comic strip collections and soon my interest in all the great old comics began to surface (it was never really buried too deep). But I never considered even trying to start doing comics myself until I saw, first, RAW and then Dead Stories, a one-shot by Mark Beyer. Those were the two catalysts that got me started doing my own comics. They were something totally new. They weren't like those dated old underground comix that were printed on cheap newsprint and full of stories about hippies doing drugs. They were beautifully printed on nice paper and featured stories and art with that late-seventies punk feel -- kind of all depressing and nihilistic. I could relate! But RAW also exhibited a knowledge and appreciation for the ART of comics. It was like they were trying to save the medium from just sliding into total crap and it was the only publication like that out there then. I saw myself as a kindred spirit so a couple years later I sent them stuff and got in. That's how it got started.

Logan: Were those comics your very first experience with writing?

Richard Sala: Actually, no. In fact, during high school I had decided I was going to be a writer. I enjoyed drawing, but I had my doubts about it as a career. I remember I had three years of high school art classes with the same teacher who was a complete bore. I was learning nothing in those classes that I hadn't taught myself at home. Luckily, for students at my high school, if your grades had been good, in your senior year you had electives, like college. So I took one class where the purpose was to read as many great books as possible and analyze them ("Developmental Reading" it was called). You read at your own pace and I read like crazy -- I had always loved to read, but suddenly I was reading stuff that challenged me and blew my mind, from Catch-22 to Dubliners -- Kafka, Vonnegut, John Barth, Samuel Beckett, Flannery O'Connor, Dostoyevsky, Rimbaud, etc, etc. The other elective I took was creative writing where I began to write short stories and even plays, believe it or not.

So when I began college in Arizona, I was an English major. My goal was to be a writer and, in fact, while I was in school I started sending in stories to magazines. It's kind of embarrassing now, but there were those sci-fi digests (do those still even exist anymore?) like Fantastic and Analog and I sent in maybe half a dozen stories, written at home on my little typewriter. They were all rejected, of course, but I got some encouraging notes from a couple of the editors. The bottom line was -- I wasn't really writing science fiction! I was just sending in kind of early versions of what I still do now -- stuff that may be mysterioso and uncanny, but certainly not sci-fi. Don't ask me what I was thinking!

So, this went on for awhile and I was getting really bored and restless with going to classes. I'd go over to the art building sometimes to look around and it seemed like so much more fun. Plus -- and I can't downplay the importance of this -- there were so many more cute girls in the art classes! In the English classes, you couldn't really meet anybody. You came to class, sat down, listened to the lecture and left. Whereas in the art classes people were casually mingling, wandering around, having coffee -- very social. So -- because you couldn't take any Art classes unless you were an Art major (a sensible ploy to keep the riffraff out). I changed my major and THAT'S how I got on the road to being an artist and not a writer!

But I always wrote, even when I was in art school. I didn't keep personal journals, but I kept notebooks filled with ideas, observations, fragments, etc, etc. So, ultimately, you can see why doing my own comics made sense to me. I loved to write and I loved to draw. The struggle was finding the best way to integrate them.

Logan: Have you ever toyed with the notion of going back and trying to write in the traditional sense again?

Richard Sala: Not really. Right now I'm happy doing what I'm doing.

Logan: A lot of your earlier work is shorter, and does have a sort of Edward Gorey feel to the rhythm. You've lately moved towards longer works -- how did that transition?

Richard Sala: My favorite writer is Kafka and I was kind of going for that oddly detached quality he has, even when writing about the most awful things. I was also reading lots of Borges and Grimm's Fairy Tales -- so when I sat down to write, what would come out was usually in a short story format. And when my comics began being published in anthologies, then suddenly more and more anthologies would ask me to contribute. That was fine, because I didn't really have any ideas for an ongoing comic book series of my own. And doing nothing but short pieces for anthologies allowed me time to start getting work as an illustrator. So, there I was, with a master's degree and no money and a painting studio in an East Oakland warehouse, a day job at a university library, a part time career as an illustrator, and a few hours left in the week to work on comics. Eventually, I gave up the painting studio and when I began making more money doing illustrations part-time than working at my day job, I quit the library, too. Then I became pretty much an illustrator first and a comic artist second.

At one point I did a serialized story for Dark Horse Comics. I'd gotten a tiny flicker of attention for having an animated serial on MTV's Liquid Television called Invisible Hands and the idea was to do a comic with a similar tongue-in-cheek-pulp-mystery-serial for an anthology Dark Horse was starting called Deadline USA. So I did Thirteen O'Clock which was eventually collected into a one-shot Dark Horse comic. I was also getting more into rediscovering and re-reading all the stuff I loved as a kid, especially all the pulp-reprint paperbacks like The Shadow and The Spider. All my old comics and monster magazines were still in boxes at my mom's house in Arizona, so I asked her to send them and that led to a real reawakening of interest in all of that.

But aside from Thirteen O'Clock I was only doing short pieces. All along I'd been doing them for myself -- for my own enjoyment. I was in a lot of really good anthologies like J.D. King's Twist and Monte Beauchamp's BLAB!, but I was in a lot of really awful ones, too, and that was always disheartening. One of things I was learning as a beginning illustrator was not to turn down any assignment. If you did, they might never call you again. So it got to be kind of the same with comics for anthologies -- I usually said yes, not so much because I was afraid they'd never call again, but because I was so grateful to have the opportunity to do comics for publication, how could I say no? And I always had ideas for stories.

But then I started to get burned out on the comics scene. There was a new anthology from Canada called Drawn and Quarterly and they asked me if I'd contribute. They were going to be printing in color -- and at that time I hadn't done any strips in color -- so I happily came on board. But when the issue came out, the color had printed horribly and the strips looked awful. Chris, the editor, assured me that they'd improve the color printing, but in the meantime, he said, maybe I should use brighter colors so they wouldn't fade out so much. I did -- but, issue after issue (I kept hoping, you see) the color looked worse and worse. It was heartbreaking. I stopped caring toward the end about the color work I was turning in to Drawn and Quarterly. (I did do one black and white strip for them that is one of my favorites, but no one else seemed to like, called "Time Bomb" -- which was indicative of where my head was at that time -- i.e. pretty crazy). I remember all that as being my first experience with knowingly turning in work that I felt was sub-standard. It was depressing -- and I was doing so well with illustration work, always busy, that I started turning down the comic anthologies. The only one I continued to work with for awhile was BLAB!, because Monte always made sure the work looked good. The irony is -- little did I know that Drawn and Quarterly would eventually lead the field in publishing really great looking books. I had the bad luck of being there before they got the bugs worked out.

Anyway -- although I pretty much stopped doing comics, I was still writing and planning and trying other things. I did a small-press book called The Ghastly Ones, for example, that I hoped would be more suited to the bookstore market than comic book stores. It wasn't a comic, but sort of an old-fashioned illustrated humor book based on those old William Steig books (like The Lonely Ones -- get it?).

Finally, it occured to me that illustration might just be a creative dead-end. I had always prided myself on working well with art directors ("hey - it's a collaborative effort!"), but as the years went on some of the little criticisms and editorial remarks got harder to take. There is much swallowing of one's pride. If you are a 35-year-old illustrator with fifteen years of work under your belt and you find yourself being given vague, nitpicky instructions on how to improve your drawing by a 23-year-old designer/art director who has absolutely no art background -- well, if you are the sensitive type it can start to get to you.

Then I happened to get the perfect call at the perfect time. Kim Thompson of Fantagraphics was starting a new anthology called Zero Zero and was doing the usual cattle-call for contributors. I told Kim that I was interested, but I didn't want to do short pieces, I wanted to do a serial. My plan was to do a long continuing story that I could eventually publish as a graphic novel. Kim said yes, and I'll be forever grateful to him for that.

So that was my first graphic novel, The Chuckling Whatsit. Because doing that had given me so much pleasure, I asked Kim if Fantagraphics would consider giving me an on-going series -- a place where I could serialize another graphic novel. Again, to my relief, he said okay -- but advised me to not ONLY have the serial, but include other material -- stories that would be complete in one issue, because serials often alienate readers. Since I didn't want to do stand-alone short stories, I came up with a character named Peculia who, in every issue, would have a self-contained adventure. So -- in that way -- I eventually, out of that series which was called Evil Eye, I got two books. I got to publish my serialized story as a graphic novel called Mad Night, and I was able to release a collection of the back-up stories, called Peculia.

After the serial had concluded in Evil Eye #12, we decided to reformat the title into a series of graphic novellas. In today's marketplace it makes more sense to produce work that can be sold in bookstores and on Amazon.com rather than just in whichever comic shop decides to carry one or two copies of it. (I'm tremendously grateful to the comic stores who HAVE supported my work over the years like Comic Relief and Meltdown, by the way - more than I can say). So - the first of those (EE #13) was a Peculia adventure called Peculia and the Groon Grove Vamires. The second will be published later in 2006 and is called The Grave Robber's Daughter.

Logan: Are you able to work on longer pieces at the same time? Peculia is a very fun read but you get a lot more depth to the story with something like The Chuckling Whatsit and Mad Night.

Richard Sala: I always like to have several projects going on at the same time and I'm always planning future ones. It's never been difficult for me to do that, I guess because I enjoy the work so much. At the moment I'm deep into working on three different graphic novels in various stages of completion. By "deep into" I mean that all three are very far along -- two have (tentative) publication dates, while the publication of the third will happen eventually (knock on wood) but its release is a little more vague for reasons that have nothing to do with me. At the same time, I enjoy doing occasional side projects -- like my pin-up girl (for the Buenaventura Press set of pin-ups by cartoonists) called Private Stash, or my "beast" drawing for the upcoming Fantagraphics Beasts book, edited by Jacob Covey.

The hardest part of balancing the work comes when a deadline for one is approaching. Then I have to give that one project my undivided attention for, say, a month or two until it's turned in.

Logan: Is there any one project you really would like to tackle at this point?

Richard Sala: This may not be exactly what you mean, but someday I'd really like to put out a graphic novel in full-color. I've done lots of color comics, but never a full-length graphic novel in color. That would be really cool. There is a project I'm involved in where that may happen, but who knows? Meanwhile, Delphine is being done in duo-tone -- that is, two colors: black line and a sepia wash. Anyway, it's just a matter of finding the right time and the right project and maybe someday I'll have some full-color books out there.

In the meantime, I'm just happy to keep working. I always have ideas for new projects -- more than I can ever actually draw, plus I like to keep myself available to do projects for whatever publisher or editor calls me up with something interesting. The best is to have a few projects going on, but still be able to take side-projects when they come up. I'm really fortunate that that's where I'm at right now.

You can purchase art from Richard Sala at his page on the ComicArtCollective.com.

You can learn more about Richard Sala at richardsala.com

Interview Conducted by E-Mail, July of 2006

Copyright © 2006 Adventures Underground