Anne Yvonne Gilbert

Colored Pencil Magic

Interview by Logan Kaufman

Yvonne was born and brought up in Northumberland, going on to study art at Newcastle College and Liverpool College of Art, where she did her diploma in Art and Design. She lectured full-time for five years and became a freelance illustrator in 1978, since when she has worked for all the major British, and more recently, US, publishers.

Yvonne was born and brought up in Northumberland, going on to study art at Newcastle College and Liverpool College of Art, where she did her diploma in Art and Design. She lectured full-time for five years and became a freelance illustrator in 1978, since when she has worked for all the major British, and more recently, US, publishers.

Her work has been featured in galleries in the UK and the US, including many solo shows, with work in collections such as Arnold Schwarzenegger, Peter Gabriel, and the Late HRH Princess Margaret.

Logan Kaufman: So many of your illustrations are fantastically elaborate. How much prep work do you have to do for each piece?

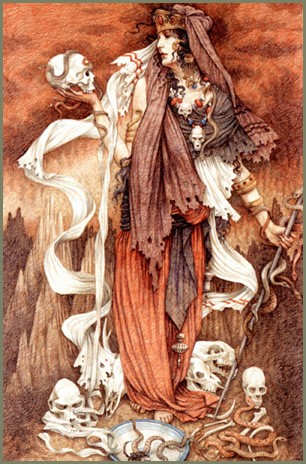

Yvonne Gilbert: That's the fun bit—once I've done my research, found my costume and reference, and photographed my model, it can become boring because all the "creativity" has already happened. I love history and costume, arms, armour, etc. so I have a lot of books on related subjects. Wherever I go I visit castles, palaces and museums, storing the information for when I may use it.

I also have a house full of costumes and props which does present problems for day-to-day living—soon I'll be packing as I am emigrating to Toronto and that really is a problem!

I need lots of models of course—I use all my friends and family in my pictures (though once or twice I have had to pick people off the streets). They have to be prepared to dress up in bits of material fashioned into costumes, holding bin-lids and broom-handles as shield and sword. I have a collection of photographs of people looking very strange—lying on the floor to appear to be flying, sitting astride sofa backs to appear to be horse-riding.

It probably takes as long to prepare an illustration—sketching roughs, e-mailing them to clients, finding models, props and reference, taking the pictures—as it does to do the finished piece, and it takes me roughly one week to complete a moderately detailed illustration.

Logan: Is it the same sort of process for animals and backgrounds, or do you have to improvise a bit more on those?

Yvonne Gilbert: Animals can be a little more difficult if I can't get the creature in front of me. I have to rely heavily therefore on other people's photos—of course, they're never in the pose I need so I take an awful lot of artist's licence! You're right—improvisation is the word.

As for backgrounds—I don't know if you've noticed but I'm not at all interested in drawing them so my figures tend to be large and fill up the space with room for just a hint of background around them.

Logan: How did you get started doing such detailed work? Was that something you always leaned toward even as a child, or an aesthetic that you enjoyed and worked toward?

Yvonne Gilbert: In my latest exhibition I have included a drawing I did when I was about five-----it's of a mermaid with shells in her hair and lots of little fishes and seaweed around her—I must always have been the same. The detail is everything and probably says more about my psychological make-up than anything. It's also to do with using pencils—it's both difficult and boring to cover large areas in flat colour—they work much better in close detail. (My style differs considerably when I paint on canvas—much less surface detail and large areas of flat paint).

Logan: I remember being blown away when I saw that you were using colored pencils, which I've always thought were a pain. When I first noticed your art in The Iron Wolf, I just assumed any little marks I was seeing were an effect you were getting from dry brushing watercolor or from egg tempura. How did you get started on that medium?

Yvonne Gilbert: You're absolutely right—they are a pain! At times I wish I'd never started—they are such an unreliable medium.

I always divide artists into two groups—those who don't mind getting their hands dirty go for paint, ink, clay and chalks; the more anally-retentive like me need to keep their hands clean and their work neat. Even as a very small child I couldn't abide mess—hence the pencils even though they do make me tear my hair out.

I actually am trying NOT to have any texture—I use the hardest pencils on the smoothest paper but the irony is that the printers don't know that and so they put it back in! Thank goodness for computers though because at least I can send files showing the art the way I want it to be.

Logan: Did you ever toy with other, cleaner, mediums like watercolor or pen and ink, or was colored pencil always the medium for you?

Yvonne Gilbert: I have used watercolours a bit—however, I gave up trying to use them on paper as I tend to "draw" with them when I discovered how beautifully they work on finely sanded thin plywood. The colours don't lift so I can keep applying layers and detail. I produced a whole book in that style—Baby's Book of Cradle Songs and Lullabies. The only time I use ink, and then it's only drawing pens, not bottles, is when I'm doing my silhouettes—which I love by the way.

Logan: Are you able to correct any mistakes with colored pencils? They don't erase, and it seems like covering up a stray mark would be pretty difficult...

Yvonne Gilbert: Correcting coloured pencil drawings is a big, big problem—you shouldn't have to alter them at all if Art-directors knew their job. I do all the preparation as line on tracing paper so that there is no erasing necessary, and get this stage approved before going any further. However I do occasionally have to make alterations—if it's a lightly drawn area I will erase it and draw over, if it's heavier I may have to make a patch. Nowadays a lot of stuff can be done in Photoshop.

Logan: Do you end up using Photoshop with your work a lot? Not just for correction, but to adjust lighting or anything, or do you try and get it all down on the paper?

Yvonne Gilbert: My Photoshop skills are rudimentary at best—I can scan, join, adjust colours and contrast and re-size to send a file but that’s about it. I have a friend, Angus McKie, who only works digitally, who is always after me to get a tablet and start drawing directly into the computer but I’ve managed to resist so far. Lack of time is my excuse.

Logan: Well, besides colored pencils being a pain, you do create a beautiful and unique look with them. Other than being clean, what do you enjoy about the medium? They're portable...

Yvonne Gilbert: I think the only advantage to the coloured pencils is that they are clean because they are very unreliably manufactured, too easily broken and sadly lacking in strength of colour (this is where Photoshop is a boon). I use Prismalo Caran D’ache and Schwan Stabilo because they are the most consistent and have harder leads—which mean they can be used with sharp points.

Logan: Is there a certain paper you find works best with them? In other media, the canvas or watercolor paper can make as much difference as the medium itself.

Yvonne Gilbert: I use as smooth a paper as I can get without being shiny—mine is Popset weave by Wiggins Teape, it’s china-filled for the printing industry. I’m trying not to show the grain of the pencil which would show starkly on cartridge paper.

Logan: One week plus all the preparation isn't a huge amount of time to complete a piece, but still, you seem very productive. How many hours a day do you put into art? Do you try and treat it like a 9-5 job, or do you jump in when the mood strikes?

Yvonne Gilbert: I work 9-5 with Radio 4 on to ward off the boredom. I would love to take longer over my work and do a really good job but money, bills and deadlines don’t allow so I’m forced into a routine and constantly going over territory where I’ve been before—not very creative I’m afraid.

Logan: You mentioned a drawing you had done as a child, and you went to school for art and design. Had you always been thinking specifically of illustration, or were you just looking at doing something creative?

Yvonne Gilbert: I was far too ignorant (always too young for my age) to know what I wanted to do, or take charge of my destiny. I went to Art College by default, because I could draw, and found myself doing illustration—again, because I could draw. My three years at Liverpool however were spent in every other department, doing every thing other than draw (which was a fantastic education actually!) and when I left I got a job teaching straight away. It was great to have some money for a change but after about four years, having met someone I knew who had an agent, I decided to try my hand at illustration.

I suppose I was influenced even subconsciously by old books my mother would buy me at jumble-sales—Arthur Rackham, Edmund Dulac, Heath Robinson etc., and of course I love books. I’m addicted to them—spend a fortune on them.

Logan: Were those you mostly drawn in by the art itself, or the stories they were illustrating?

Yvonne Gilbert: I have a visual memory rather than one for words so it has to have been the pictures—I have vivid memories of certain pictures and sitting studying them intensely. Under the age of five it was as if the pictures were real and I could get into them. As I got older the words and stories themselves became more important and I could visualize my own pictures.

Logan: What did you teach after you graduated?

Yvonne Gilbert: I was teaching drawing to 15- to 18-year-olds at a local technical college—I really enjoyed it. I’ve always said you haven’t learned anything until you try to show someone else how to do it.

Logan: Did any of your students go on to great achievements that you know of?

Yvonne Gilbert: Charlotte Voake and Louise Brierley were students of mine.

Logan: I assume your friend introduced you to their agent? Was that your first "in" to the illustration field?

Yvonne Gilbert: My friend had mentioned he was with Artist Partners so I contacted them myself. Fortunately John Barker recognised something in my work and “groomed” me as an up-and-coming—something which would never happen these days. John has long since died but I’ll never forget his faith in me—he “invented” my first job by persuading the Telegraph Magazine to commission me to draw six celebrities as the historical character they would have most wanted to be.

Logan: Were you fairly nervous about your working appearing in print for the first time?

Yvonne Gilbert: Naively I didn’t foresee the mangled attempts to reproduce my work or the god-awful type vomited over the top. Thank goodness for Photoshop and being able to prepare digital files ourselves—especially as Danny is a graphic designer obsessed by type. I have always been disappointed in the finished results and my ambition is to do some books that I want to do and make sure they meet my standards.

Logan: What kind of projects do you have in mind?

Yvonne Gilbert: My ambition is to work with my husband as designer/illustrator/packagers where I do the pictures and he does the rest—that way the book looks like it is supposed to! We have just finished the Frog Prince together and are going to do The Mitten now—when we have five or six good ones under our belt we will be better able to dictate terms. We work very well together (and would like to spend more of our working hours together)—we share an excitement for what we do.

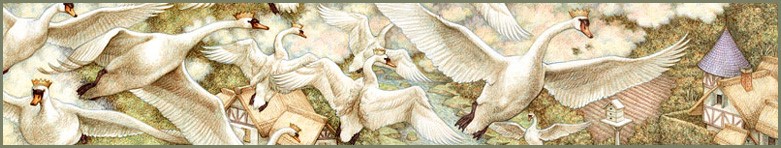

For The Mitten I am changing my style radically as there is less money upfront for a greater share of the royalties—my usual problem being the time it takes me to do the illustrations versus the money I have to live on. I have had a lot of fun working differently—see attached—the red areas should of course be flat colour—the only bits of shading in the book will be the faces and perhaps the feet of the animals. It’s a chance for me to squeeze in some silhouettes, too.

Logan: Would you be self-publishing then, or just trying to get a finished product and submitting them around rather than doing contract work?

Yvonne Gilbert: We will go through existing publishers—the problem with self-publishing is the distribution. We have a friend, Helen Limon at Zedsaid Publishing who has sold her house to set up her own publishing company and her biggest hurdle is how to get the product into the shops. When she has cracked how to deal with the big distributors, etc., perhaps we’ll give self-publishing a go.

At present the goal is to be working on our own ideas rather than commissions so we’ll have to keep playing with the big boys.

Logan: Are you just concentrating on adapting classic stories, or do you write as well?

Yvonne Gilbert: I do write sometimes (in my own way) and I have some things started, but you know—I don’t think I’ll ever do anything with them. There are far too many lovely stories anyway that I would love to work on. Today I am going to work on a plan for my silhouette Beauty and the Beast, and look at the contract for The Mitten, as Mitten Press likes the new treatment.

Can I say, however, that many children’s books are so badly written that I encourage all other illustrators to write their own stuff—I wonder what the editors are doing? I don’t mean the classics, I mean the majority of trashy picture-books that both look and sound the same. I was appalled on my only trip to Bologna so far to see that most of these were on the British stands! The general standard is appalling and the ideas mundane in the extreme.

Logan: I assume you're talking about the thousands of "Grandma dies and I learn a valuable lesson" type books?

Yvonne Gilbert: The mundane-ness is mind-numbing don’t you think? How patronising to assume that children lack the intelligence to absorb complex themes and emotions! I know how much I enjoyed stories and ideas from a very young age, my son too. I think that by fearing they may be talking above the children’s heads they are paralyzing them with boredom—no wonder many children are “off” books—compare them to the wonderful stuff seen at the cinema or on TV. The same attitude prevails in illustration—art directors insist on simple, brightly-coloured daubs and cartoon-like characters for the sake of the children—I distinctly remember the emotions I had when looking at Arthur Rackham when I was very small—the enjoyment of studying a picture closely to “find” all the details.

Logan: What do you see in the classics that you don't see in a lot of today's books?

Yvonne Gilbert: That’s easy—POETRY! The language, the ideas, the intricacy of the tale—never mind who can follow the plot or not. These stories are meant for all ages to enjoy and understand at the level of their own personal experience. Who was it that said we need to read at a higher level than that is comfortable? I think that’s a very good point—children need to be challenged and intrigued.

Logan: Do you think that mainly falls on the publishers and editors? It seems like there are any number of creative people out there—maybe just not doing children's books...

Yvonne Gilbert: I think the main problem with publishing is that it is a hopelessly old-fashioned, conservative, reactionary business! There are great publishers and fantastic editors and art-directors but they seem to be the exception that proves the rule. Most of the art-directors I meet are young and straight from school or college and see their job as perpetuating the status-quo—in fact over here they are mostly called Daphne or Caroline and are between finishing school and a good marriage! It is hardly a “creative” business—most publishers do little but copy what another is doing—look at all the fake “-ologies” springing up everywhere.

Their other major shortcoming is their refusal to market their product. How many picture-books are actively advertised or placed as point-of-sale? Hardly any—the only way I can find most of my picture-books in a shop is to order them. They rely too much on covering their costs with the foreign co-editions so that there is no incentive to get out there and sell.

Logan: There are definitely good kids books out there though, with maybe just a few too many falling through the cracks and only seeing a single printing. The Brave Little Tailor by Dugin was an excellent book from the last few years and is out-of-print. What would you like to see change?

Yvonne Gilbert: I’m not even aware of that one—that’s the trouble—if they aren’t seen on the shelf how are we supposed to buy them or even know about them.

How to change things is the great conundrum—more and more of us are looking for ways to take over creatively. I have a friend Helen Limon who has set up as her own publishing company (HYPERLINK "http://www.zedsaid.co.uk/"www.zedsaid.co.uk) with great critical acclaim but is still trying to crack distribution. Self-publishing is cheap and easy but the problem remains of how to get them on the shelves—I can’t see a way round this yet but instead of accepting what is offered I have determined to be pro-active as with Beauty and the Beast etc. My hope is that when Danny and I have a few good books under our belts, and hopefully some good sales, we can make a reputation for ourselves as book-designers. Where that may lead to I don’t know but I do believe it should be possible to influence the industry from inside.

The idea of one-off art books is rather appealing too—should we find ourselves financially able we will definitely be trying that too—there is a fair here in London where such things can be sold.

Meanwhile I will stay on my hobby-horse as I think the industry is almost criminal in its neglect of talent—the standard of illustration is extremely high (not reflected on the shelves) and picture books more popular than ever. Unfortunately many ideas and most of the “creativity” resides on the other side of the fence and a lot publishers are too arrogant to admit this.

Logan: Touching on the aspect of books not being seen, I suppose this is a fault of the bookstores as well. Most bookstores have a place for new releases and bestsellers, but you'll never see kids books on those shelves that are up front.

Do you try and market your books on your own when they are released? Signings and readings and so-forth?

Yvonne Gilbert: I do as much as I can—unfortunately when you rush to suggest a book-signing or some such you’re looked upon here as trying to blow-your-own-trumpet—you know how the Brits seem to hate success. I answer all emails from school children and students, I mentor any student that asks, I attend all writer/illustrator group activities, I do my own PR mail-outs, I give many free hours to schools and colleges—in other words I do anything I can think of to promote illustration and illustrators. I’ve become quite good at getting the attention of the press and local media through all this. The National Centre for the Children’s Book (seven stories) opened here in Newcastle a few years ago and I give them as much support as I can—though they were very cold at first, again a very British reaction. It’s hard to know what else to do.

Logan: For us, selling a lot of one item that isn't being pushed by the media is probably ten copies or less—which certainly isn't going to keep a book in print, unfortunately. When we're buying for the shop, unless a book has a great cover or you lucked into a magnificently done blurb, your book probably isn't going to get ordered much, if at all. I think you are right in that it really needs to be a top down message from the publishers, that children's books are important. Do you think publishing fewer titles would help, or would that just result in them narrowing their vision further on what they consider a safe sell?

Yvonne Gilbert: We could certainly do without all that crap—think of all those trees—I somehow don’t think we’ll persuade them though. Goodness knows what the answer is—I’d love to be a “fly-on-the-wall” to see what’s really going on—I would imagine it’s all down to budgets—the children’s department will be allocated so much, they’ll have a target of so many books, they’ll divide the first sum by the second and do whatever they can afford (they always plead poverty). It must therefore be mostly down to ignorance and lack of education that result in such poor quality overall—I’m damn sure we could do better with the resources available—there’s just no excuse, is there?

Logan: Do you see much success when you market yourself outside of children's books? People noticing your stamps, posters, or book covers?

Yvonne Gilbert: I have much more success outside of children’s publishing—I’ve won all the major awards but I don’t think I’ve ever won anything with my books. That’s why I’m so bloody determined to succeed!

Logan: Do you get much carry over then? In sci-fi art and graphic novels and such, artists can develop quite the following where anything they've touched will sell. Or do you even having a way of knowing how much cross-genre interest you get?

Yvonne Gilbert: I doubt that very much—there are people that buy my books but they wouldn’t necessarily know anything about my other work. The best feedback I get is through my website when people take the trouble to e-mail me (I get tons of Photoshop groups asking permission to play around with stuff), I get a lot of requests for prints of the Blue Angel, slightly less for Relax. I’m only surprised that anyone pays attention—most of my work just seems to disappear into a black hole.

Logan: With all the headaches of getting your work noticed and dealing with publishers, do illustrators have daydreams about working in offices?

Yvonne Gilbert: At really bad times when work has been very scarce or no one has paid me for months I wish like mad that I’d chosen a more secure job. I don’t think people have any idea how difficult it is especially since the whole of society as far as banking and bill paying is concerned is geared-up for people with monthly salaries. I’ve always said they should make everyone self-employed—society would change radically—I also think it would become much more productive. I suppose the real dream is a private income—I do know some lucky people who were born with money! The second way to do it is marry someone with a good income—Nichola Bailey’s husband is a barrister. The third way is to get a plum lecturing position—why did I choose the most difficult route?!

You can learn more about Anne Yvonne Gilbert at yvonnegilbert.com

Interview conducted by email, January of 2007

Copyright © 2007 Adventures Underground

More Interviews